Cesarean Section - A Brief History

Part 3

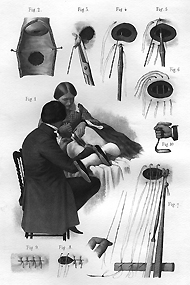

Once anesthesia, antisepsis, and asepsis were firmly established obstetricians were able to concentrate on improving the techniques employed in cesarean section. As early as 1876, Italian professor Eduardo Porro had advocated hysterectomy in concurrence with cesareans to control uterine hemorrhage and prevent systemic infection. This enabled him to reduce the incidence of post-operative sepsis. But his mutilating elaboration on cesarean section was soon obviated by the employment of uterine sutures. In 1882, Max Saumlnger, of Leipzig made such a strong case for uterine sutures that surgeons began to change their practice. Saumlnger's monograph was based largely on the experience of U.S. healers (surgeons and empirics) who had used internal sutures. The silver wire stitches he recommended were themselves new, having been developed by America's premier nineteenth-century gynecologist J. Marion Sims. Sims had invented his sutures to treat the vaginal tears (fistulas) that resulted from traumatic childbirth.

As cesarean section became safer, obstetricians increasingly argued against delaying surgery. Rather than waiting for many hours of unsuccessful labor, doctors such as Robert Harris in the United States, Thomas Radford in England, and Franz von Winckel in Germany opted for an early resort to the operation in order to improve the outcome. If the woman was not in a state of collapse when taken to surgery her recovery would be more certain, they claimed. This was an argument sweeping through the general surgical community and one that resulted in greater numbers of operations on an expanding patient population. In obstetrical surgery the new approach also assisted in reducing maternal and perinatal infant mortality rates.

As surgeons' confidence in the outcome of their procedures increased, they turned their attention to other issues, including where to incise the uterus. Between 1880 and 1925, obstetricians experimented with transverse incisions in the lower segment of the uterus. This refinement reduced the risk of infection and of subsequent uterine rupture in pregnancy. A further modification -- vaginal cesarean section -- helped avoid peritonitis in patients who were already suffering from certain infections. The need for that form of section, however, was virtually eliminated in the post World War II period by the development of modern antibiotics. Penicillin was discovered by Alexander Fleming in 1928 and, after it was purified as a drug in 1940, became generally available and dramatically reduced maternal mortality for both normal and cesarean section births. Meanwhile, the low cervical cesarean section, advocated in the early twentieth century by the British obstetrician Munro Kerr, had become popular. Promulgated by Joseph B. DeLee and Alfred C. Beck in the United States, this technique reduced the rates of infection and of uterine rupture and is still the operation of preference.

In addition to surgical advances, the development of cesarean section was influenced by the continued growth in number of hospitals, by significant demographic changes, and by numerous other factors -- including religion. Religion has affected medicine throughout recorded history and, as noted earlier, both Jewish and Roman law helped shape early medical practice. Later, in early to mid-nineteenth century France, Roman Catholic religious concerns, such as removal of the infant so that it could be baptized, prompted substantial efforts to pioneer cesarean section, efforts launched by some of the country's leading surgeons. Protestant Britain avoided cesarean section during the same period, even though surgeons were experimenting with other forms of abdominal procedures (mainly ovarian operations). British obstetricians were far more inclined to consider the mother primarily and, with cesarean section maternal mortality over fifty percent, they usually opted for craniotomy.

As the rate of urbanization rapidly increased in Britain, throughout Europe, and the United States there arose at the turn of the century an increased need for cesareans. Cut off from agricultural produce and exposed to little sunlight, city children experienced a sharply elevated rate of the nutritional disease rickets. In women where improper bone growth had resulted, malformed pelvises often prohibited normal delivery. As a result the rate of cesarean section went up markedly. By the 1930s, when safe milk became readily available in schools and clinics in much of the United States and Europe, improper bone growth became less of a problem. Yet, many in the medical profession were slow to respond to the decreased need for surgical delivery. After World War II, in fact, the cesarean section rate never returned to the low levels experienced before rickets became a large-scale malady, despite considerable criticism of the too frequent resort to surgery.

The safe milk movement was a measure of preventive medicine promoted by public health reformers in the United States and abroad. These reformers worked with governments to improve many aspects of maternal and infant health. Yet while more and more women received prenatal attention -- indeed more than ever before -- surgical intervention continued to rise. So too did the involvement of state and federal governments in financing and overseeing maternal and fetal care. Accompanying these trends was a tendency over the past half century for the status of the fetus increasingly to be given center stage.

Since 1940, the trend toward medically managed pregnancy and childbirth has steadily accelerated. Many new hospitals were built in which women gave birth and in which obstetrical operations were performed. By 1938, approximately half of U.S. births were taking place in hospitals. By 1955, this had risen to ninety-nine percent.

During that same period medical research flourished and technology was greatly expanded in scope and application. Advances in anesthesia contributed to improving the safety and the experience of cesarean section. In numerous countries, including the United States, spinal or epidural anesthesia is used to alleviate pain in normal childbirth. It has also largely replaced general anesthesia in cesarean deliveries, permitting women to remain conscious during surgery. It results in better outcomes for mothers and babies and facilitates immediate contact and bonding to occur.

These days, too, fathers are able to make that important early contact and support their partners during both normal and cesarean births. When childbirth was moved from homes to hospitals fathers were initially removed from the birthing scene and this distancing became even more complete in relation to surgical delivery. But, the use of conscious anesthesia and the increased ability to maintain an antiseptic and antibiotic field during operations allowed fathers to be present during cesarean section. Meanwhile, changes in gender relations were altering the involvement of many fathers in pregnancy, childbirth, and parenting. The modern father participates in childbirth classes and seeks a prominent role in birthing -- normal and cesarean.

Currently in the United States slightly more than one in seven women experiences complications during labor and delivery that are due to conditions existing prior to pregnancy; these include diabetes, pelvic abnormalities, hypertension, and infectious diseases. In addition, a variety of pathological conditions that develop during pregnancy (such as eclampsia and placenta praevia) are indications for surgical delivery. These problems can be life-threatening for both mother and baby, and in approximately forty percent of such cases cesarean section provides the safest solution. In the United States almost one quarter of all babies are now delivered by cesarean section -- approximately 982,000 babies in 1990. In 1970, the cesarean section rate was about 5%; by 1988, it had peaked at 24.7%. In 1990, it had decreased slightly to 23.5%, primarily because more women were attempting vaginal births after cesarean deliveries.

How can we explain this dramatic increase? It certainly far exceeds any rise in the birth rate, which went up by only 2% between 1970 and 1987. In fact there were several factors that contributed to the rapid rise in cesarean sections. Some of the factors were technological, some cultural, some professional, others legal. The growth in malpractice suits no doubt promoted surgical intervention, but there were many other influences at work.

Last Reviewed: March 6, 2024