Darwin’s Life continued

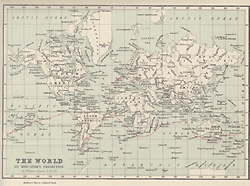

Map of the Beagle voyage, in Charles Darwin, Journal of researches, 1898 edition

South America was Darwin’s playground and field study for the next four years: Brazil, Uruguay, Argentina, Chile, Peru, and Ecuador. His “first encounters” there embraced the natural and social worlds: fossil mammals and flightless birds—black slavery and stone-age natives—earthquakes, volcanoes, and tidal waves. By September 1835 the expedition had landed at the Galápagos Islands, a ready-made experimental station. For just over a month, Darwin crawled in the hot sun amidst the tortoises, iguanas, finches, mockingbirds, and scrub. Only in the calm of later study would he see new patterns coming out of what he found in this isolated cluster of islands. Speeding eastward home, the Beagle spent the next year calling at Tahiti, New Zealand, Australia, South Africa, and islands in between, touched at Brazil and the Azores, and finally sailed into Falmouth in Cornwall on October 2, 1836. Darwin had been gone four and three-quarters years.

After this great voyage, Darwin settled down. A member of wealthy family, he was free to work on his science. He set about putting his personal life in order. In January 1839, he married Emma Wedgwood (1808-1896), a long-standing friend (and relative—they were both grandchildren of Josiah and Sarah Wedgwood [1734-1815]). By September 1842 the family had moved to Down House, some 15 miles southeast of London, never to move again. Indeed Darwin never left England again, and rarely left home, except to participate in the life of science in London, or to recuperate his health at a spa. With Emma he fathered ten children over the next seventeen years. For the rest of his life, some 46 years after the Beagle voyage, he relentlessly pursued his science amidst debilitating chronic illness. His reputation expanded with a stream of solid works in geology, natural history, and even psychology and anthropology. His expedition narrative, The Voyage of the Beagle, which he produced in 1839, has never gone out of print. And for twenty years he labored on the work for which he is best known, the work that changed the world: On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection.

Darwin’s life after the Origin was one of research and writing—ten more books, based on his Beagle observations, his voluminous reading, and on the careful experiments he set up at his home. He wrote his Autobiography, originally published for his children and grandchildren only, but later made public. The autobiography laid out a life devoted to science, a life enmeshed in a rich web of correspondents and visitors. Later in life, he was lionized by the scientific community, yet his opponents won the debate within government. No state honors came his way, not even a knighthood. However, when Darwin died on April 19, 1882, he was honored with a state funeral and interment in Westminster Abbey—Joseph Hooker, Thomas Henry Huxley, and Alfred Russel Wallace serving as pallbearers. Darwin’s place in the public mind was secured.

Last Reviewed: May 8, 2014