Maimed Men

"The limbs of soldiers are in as much danger from the ardor of young surgeons as from the missiles of the enemy."

Surgeon Julian John Chisholm, 1864

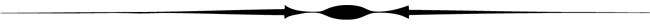

Amputation being performed in front of a hospital tent, Gettysburg, July 1863

Courtesy National Archives and Records Administration

Although the exact number is not known, approximately 60,000 surgeries, about three quarters of all of the operations performed during the war, were amputations. Although seemingly drastic, the operation was intended to prevent deadly complications such as gangrene. Sometimes undertaken without anesthesia, and in some cases leaving the patient with painful sensations in the severed nerves, the removal of a limb was widely feared by soldiers.

Under the Knife

At this time, most of the vast numbers of wounded men made it impossible for surgeons to undertake more delicate and time-consuming procedures such as building splints for limbs or carefully removing only part of the broken bone or damaged flesh. Critics, like Confederate surgeon Julian John Chisholm, charged that inexperienced doctors were too eager to attempt amputation as a way to improve their skills, and accused them of experimenting, often exacerbating existing injuries. Soldiers nicknamed such enthusiasts "butchers" and some even went so far as to treat themselves to try to avoid the painful intervention of the surgeon.

"The Civil War Surgeon at Work in the Field," Winslow Homer's heroic image of medical care in the chaos of the battlefield, 12 July 1862

Courtesy National Library of Medicine

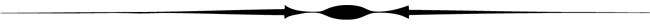

A Manual of Military Surgery, Confederate States of America, Surgeon General's Office, 1863

Courtesy National Library of Medicine

The Limits of Medicine

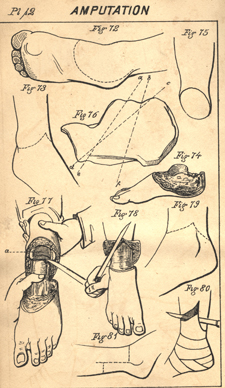

Private George W. Lemon, from George A. Otis, Drawings, Photographs and Lithographs Illustrating the Histories of Seven Survivors of the Operation of Amputation at the Hipjoint, During the War of the Rebellion, Together with Abstracts of these Seven Successful Cases, 1867

Courtesy National Library of Medicine

Most physicians had a very limited understanding of the importance of sterilization and the risks of infection, and little practice treating the kinds of major cases seen during the war. Some severe wounds, particularly those to the stomach, were usually fatal so patients unlikely to recover were often left untreated. Injured soldiers often waited more than a day for medical care, and sometimes had to endure repeated procedures to remove infection or for hastily undertaken amputations to be properly finished.

Private George W. Lemon was shot in the leg at the battle of the Wilderness on May 5, 1864. He was captured by Confederate soldiers and did not receive treatment for his injuries until he was freed by Union forces over a week later. For more than a year he suffered repeated infections in the wound and poor health, until Surgeon Edwin Bentley amputated the limb. The soldier made a full recovery and was fitted with an artificial leg in 1868.

Private George W. Lemon, from George A. Otis, Drawings, Photographs and Lithographs Illustrating the Histories of Seven Survivors of the Operation of Amputation at the Hipjoint, During the War of the Rebellion, Together with Abstracts of these Seven Successful Cases, 1867

Courtesy National Library of Medicine

Private George W. Lemon, from George A. Otis, Drawings, Photographs and Lithographs Illustrating the Histories of Seven Survivors of the Operation of Amputation at the Hipjoint, During the War of the Rebellion, Together with Abstracts of these Seven Successful Cases, 1867

Courtesy National Library of Medicine