Biographies

Mathieu Joseph Bonaventure Orfila (1787–1853)

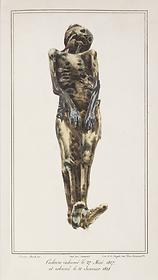

Mathieu Joseph Bonaventure Orfila (1787–1853), often called the "Father of Toxicology," was the first great 19th-century exponent of forensic medicine. Orfila worked to make chemical analysis a routine part of forensic medicine, and made studies of asphyxiation, the decomposition of bodies, and exhumation. He helped to develop tests for the presence of blood in a forensic context and is credited as one of the first people to use a microscope to assess blood and semen stains. He also worked to improve public health systems and medical training.

Born a Spanish subject, on the island of Minorca, Orfila first studied medicine in Valencia and Barcelona, before going to study in Paris. His first major work, Traité des poisons tirés des règnes minéral, végétal et animal; ou, Toxicologie générale, was published in 1814. After a failed attempt to set up chemistry professorships in medical colleges in Spain, he returned to France. In 1816, he became royal physician to the French monarch Louis XVIII. In 1817 he became chemistry professor at the Athénée of Paris, and published Eléments de chimie médicale, on medical applications of chemistry. In 1818 he published Secours à donner aux personnes empoisonnées ou asphyxiées, suivis des moyens propres à reconnaître les poisons et les vins frelatés et à distinguer la mort réelle de la mort apparente. In 1819 he became a French citizen and was appointed professor of medical jurisprudence. Four years later, he was made professor of medical chemistry.

He became dean of the Faculty of Medicine in 1830 and reorganized the medical school, raised educational requirements for admission, and instituted more rigorous examination procedures. He also helped to establish hospitals and museums, specialty clinics, botanical gardens, a center for dissection in Clamart, and a new medical school in Tours.

During his long career, Orfila was called to act as a medical expert in widely publicized criminal cases, and became a notable and sometimes controversial public figure. Exacting in his methods, Orfila argued that arsenic in the soil around graves could be drawn in to the body and be mistaken for poisoning. He conducted many studies and insisted that testing of soil be part of the procedure in all exhumation cases.

He was a prominent member of the Parisian social and intellectual elite, and a regular attendee (and host) of salons in the 1820s and 1830s. But his zealous activities as dean, his prolific writings on polarizing issues, and his ardent pro-monarchist politics made him numerous enemies. After he was removed from his post as dean during the 1848 revolution, a commission was set up to investigate illegal or irregular acts during his tenure, but found none. By 1851, he was rehabilitated and elected president of the Academy of Medicine.