About a hundred years ago, public health took a visual turn. In an era of devastating epidemic and endemic infectious disease, health professionals began to organize coordinated campaigns that sought to mobilize public action through eye-catching wall posters, illustrated pamphlets, motion pictures, and glass slide projections.

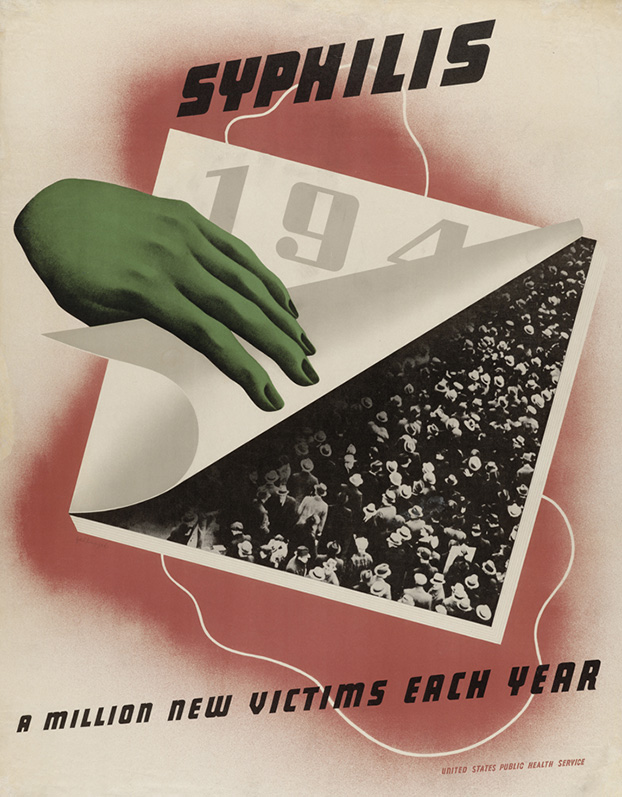

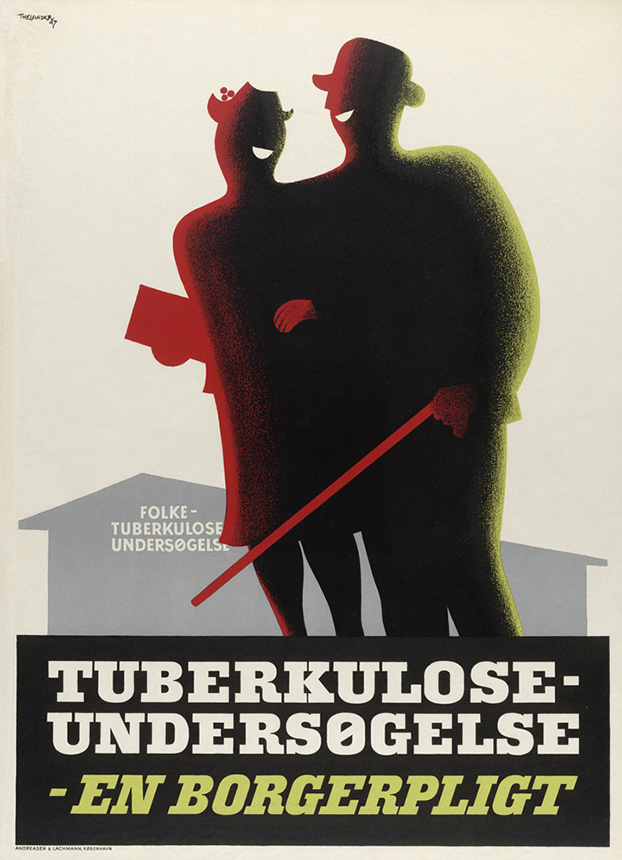

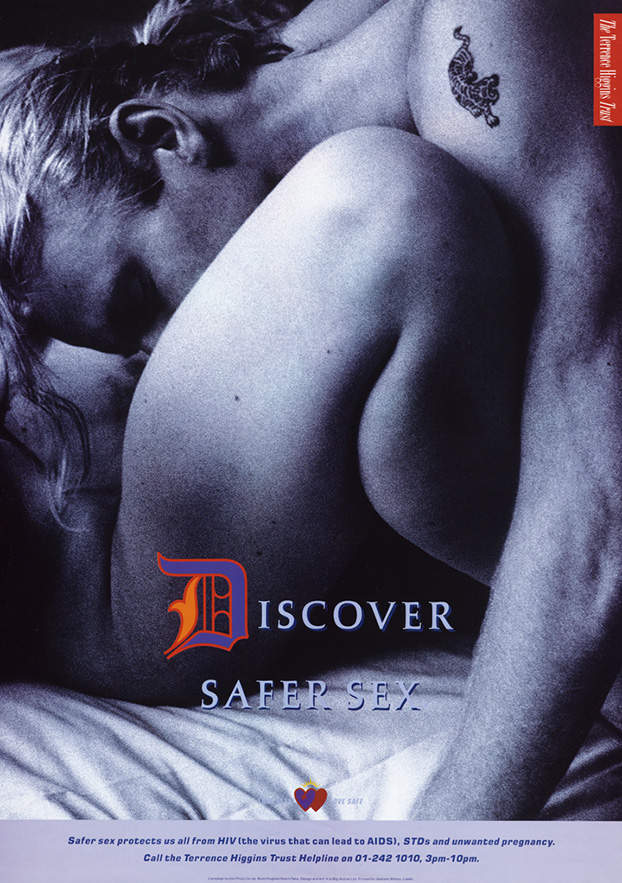

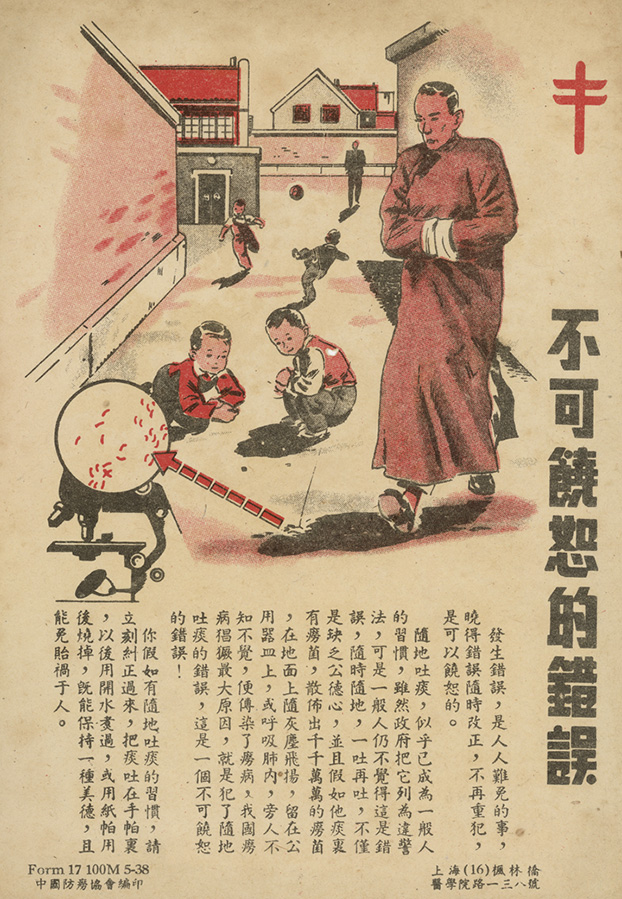

Impressed by the images of mass media that increasingly saturated the world around them, health campaigners were inspired to present new figures of contagion and recycle old ones, using modernist aesthetics, graphic manipulations, humor, dramatic lighting, painterly abstraction, distortions of perspective, and other visual strategies.

Health Campaigns

Health Posters

The Origin of the Poster

The use of poster campaigns, with visually compelling graphics and slogans, originated in the mid-1800s in Western and Central Europe and North America. Wall posters and billboards were deployed in mass media campaigns to advertise theatrical performances, sell products, or propagandize for candidates and parties in political elections. A new visual culture emerged, and a new group of professionals participated in it: commercial artists, graphic designers, marketers, consultants. By the early 20th century, a riot of images festooned the walls, kiosks, and streets of Europe and North America.

The Spread of the Health Poster

As health departments, philanthropies, and political health advocacy groups organized and professionalized, they took on the mission of changing public behavior, gaining funding, and mustering political support. To educate and alert the public, they adopted the tactic of wallpostering in conjunction with lectures, pamphlets, exhibition displays, health mobiles, slide shows, films, and other media. The result was a proliferation of health posters, and a proliferation of visually compelling images of disease and disease agents — which became a distinctive practice of the modern health campaign. Health posters spoke in the idiom of the larger visual culture of graphic design, using artists and designers who worked for magazines, newspapers, and advertising agencies.

What are health posters designed to do?

The first job of the health poster is to recruit the viewer’s gaze. Like the commercial advertisement—which disturbs, seduces, entertains, annoys—the health poster will do almost anything to get the attention of its public. The cultural expectation is that the health poster—like the commercial advertisement—will exert a powerful effect on the behavior of the public.

Through a combination of rational argument and emotionally affecting imagery, the health poster will persuade or motivate viewers to carry a handkerchief, see a doctor, get an x-ray, use a condom, refrain from drinking unsanitary water, get vaccinated, give money to a health advocacy organization, etc. The different styles, approaches, and figurations reflect differing views of what posters can do.

Each poster belongs to a singular historical and cultural moment: a particular health campaign, disease, institution, or set of professional and public constituencies. Each poster is produced in unique circumstances that reflect the technical abilities and expectations of the artists, designers, sponsors, and audience. But the poster always does more than just spread a stated message about health. It also conveys ideological, cultural and moral assumptions about gender, politics, race, class, and/or society.

What do health posters actually do?

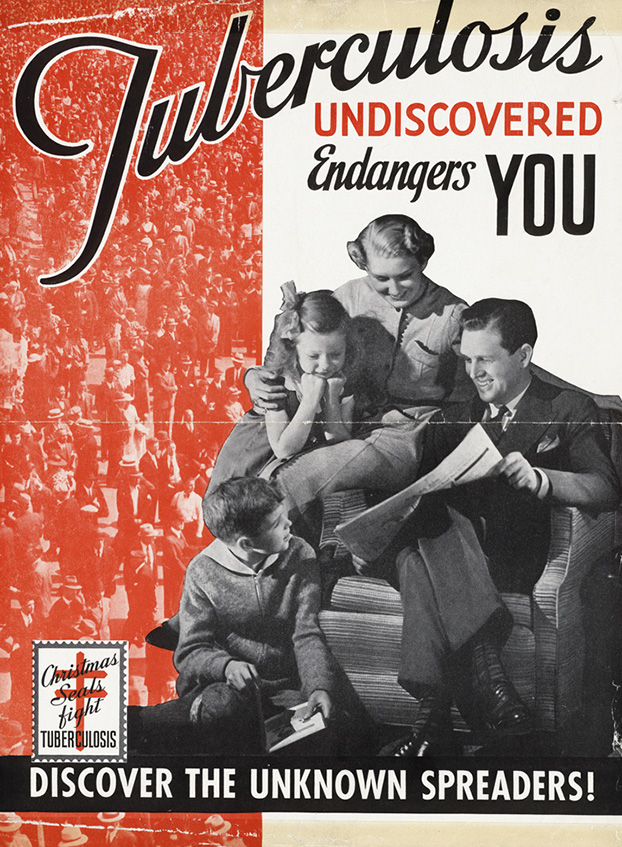

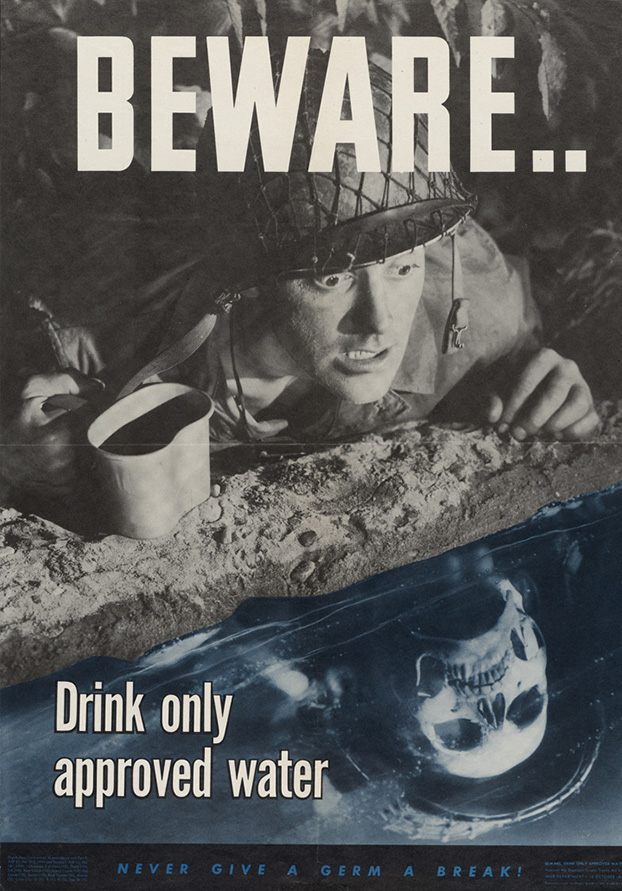

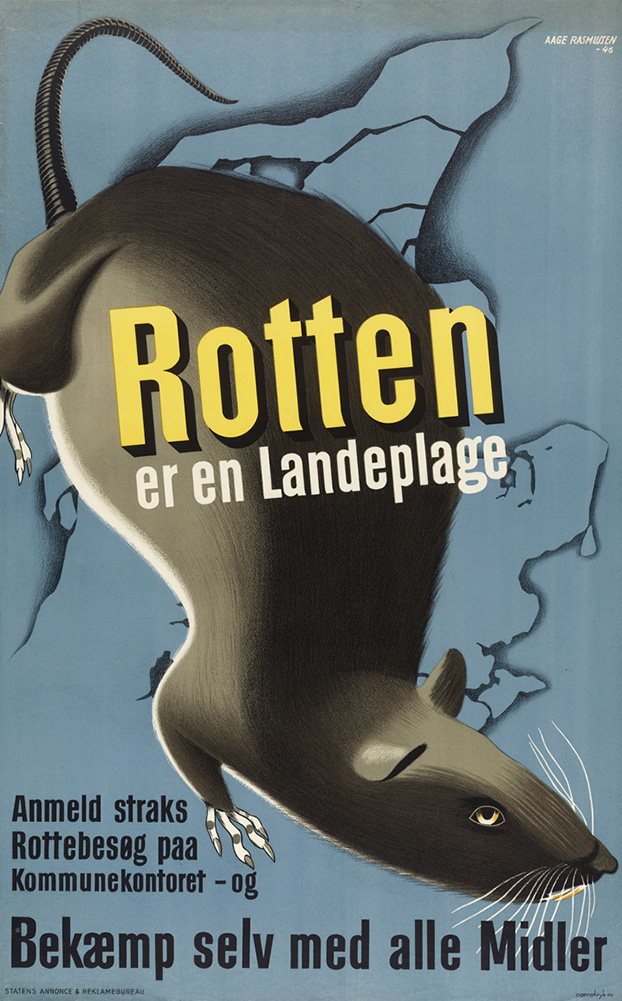

Some posters attempt to incite anxiety. Health posters often represent contagion through an iconography of death: skulls, skeletons, shadows. They communicate the proliferation of disease, spread by ominous agents. They depict society as beset by germs, flies, rats, mosquitoes, prostitutes, swarming masses of humanity, even seemingly innocent figures such as little girls or old men. The disease agent is not us, but something else, an “Other.” Even so, we may harbor it within our bodies and unintentionally spread it by our conduct.

But the posters also offer reassurance. Collective and individual action, under the guidance of medical authority, are depicted as effective counters to disease. The health campaign, not wanting to scare the viewer off by showing the horrors of disease, often ridicules or domesticates the disease agent. The thing that kills is the thing that visually entertains.

Since the opening years of the 20th century, health professionals have been impressed with this advertising model. Visually compelling ad campaigns measurably increase sales. But advertising is not an exact science, and reasons for the effectiveness of particular advertising images are often difficult to discern.

Health behavior is complex, and much is at stake. Health campaigns often have limited budgets and usually cannot saturate the media; even if they do, the public can always ignore them. History shows that mass media health campaigns best succeed as part of coordinated mobilizations that involve public health workers, communities, government officials, and grass-roots activists at the local, regional, national and international levels.

Contagion and Visual Culture

Infectious diseases are dramatic, dynamic, and often unpredictable. They affect every individual and every population. They reveal the intimate exchanges between individuals and among networks of individuals. Through contagion, they link us. They have changed the outcome of wars, destroyed economies and societies, spawned social upheaval, shifted the demographic profiles of countries, and shaped history. And they remain with us, still making front page news as they exploit new vulnerabilities in human populations. Science has revealed many facts about microbes and infections, yet many mysteries remain.

Hans Zinsser, in his classic book, Rats, Lice and History published in 1934, wrote: “Infectious disease is one of the great tragedies of living things—the struggle for existence between different forms of life.” This struggle has inspired imagination and creativity of visual artists who have portrayed this continuing saga in many ways over the centuries.

Health posters provide a window through which the recent history of infectious diseases can be viewed. They show the diseases, the health problems, and the public health responses that have preoccupied health leaders over the years. They provide context and a setting; some tell a story. Each is the product of a specific time and culture, though some images seem to evoke universal comprehension: skulls, skeletons, the image of the Grim Reaper, and the representation of microbes as ugly demons or monster-like creatures. Not surprisingly, several of these posters focus on some of the gravest infectious disease scourges of the 20th century, including tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS. Sadly, these two infections remain major killers globally.

Different infectious diseases carry different moral weight. Influenza is just “flu,” but plague was the Black Death and tuberculosis the White Plague. Infections that carry stigma are typically those that are transmitted sexually (HIV/AIDS, syphilis, gonorrhea) or via intravenous drug use (e.g., HIV/AIDS), or are associated with poverty and crowding (tuberculosis), poor sanitation (cholera), or disfigurement (leprosy). Stigma typically results in patients being rejected and isolated beyond what is needed to prevent spread of infection.

It is revealing that the posters about venereal disease from the 1940s depict the woman as the villain—the source of sexually transmitted infection for the theoretically “clean” man. The message portrayed was that wily women, whether the seductress or the young woman appearing innocent, could tempt unwary men and trap them with sexually transmitted infections. Women were suspect, deceptive and dangerous, and the savvy man was to stifle his sexual desires.

With HIV/AIDS, condoms came out of the closet and from behind the pharmacy counter. Now condoms could be depicted on a poster, described in public advertisements, distributed as favors at events, and shown in places of social gathering. A whimsical poster that the Brazilian Ministry of Health used in a media campaign to counter statements by religious leaders questioning whether condoms worked showed a knotted, inflated condom filled almost completely with water and with a goldfish swimming in it—a symbol of life, renewal, continuity, hope, and suggesting an impenetrable characteristic of the condom. The message “Nothing passes through a condom. Use it. Trust it.”

If AIDS exposed condoms, SARS similarly propelled face masks into the public consciousness. More than any other recent infection, SARS moved face masks out of the hospital and into ads, onto covers of magazines, and on posters. In an earlier era, during the influenza pandemic of 1918 and 1919, face masks were also displayed on posters and in public health alerts.

While many of the early posters provide messages about dangers and activities or people to avoid, the HIV posters show a distinct reversal. One depicts the ways that HIV cannot be spread with the implicit message that contact with HIV-infected individuals is safe. This is meant to allay fears and allow interactions that some had curtailed because of fear. Another showed expression of affection that would be safe - a contrast from the moralistic rendering of sex.

Most of the posters in this collection focus on infections that are transmitted from person to person and via vectors. A 1995 World Health Organization report broke down the 17.3 million deaths globally that year from infectious diseases, according to mode of transmission, and found that 65% were caused by microbes transmitted from person to person (like tuberculosis and HIV/ AIDS). About 22% were foodborne, waterborne, or soil borne (cholera and typhoid fever) and about 13% were transmitted by mosquitoes, such as malaria. One of the deadliest diseases transmitted person-to-person is tuberculosis.

Anti-tuberculosis societies, which began more than a century ago, were instrumental in educating the public. The National Association of the Study and Prevention of Tuberculosis formed in the U.S. in 1904 was renamed the National Tuberculosis Association (NTA). It attempted to base health messages on the best science available at the time. The NTA borrowed devices and approaches developed by advertising and business agencies and developed others of its own. In 1906, exploiting the concept of a trademark used by companies, such as Quaker Oats, it adopted the double-barred Lorraine cross as its symbol. This was used on advertising, on posters, and on toilet articles sold to raise money for tuberculosis patients. The symbol was also used on Christmas seals sold to raise money. The NTA used simple slogans, trying to make messages short and memorable (Don’t spit!). It is noteworthy that the double-barred cross symbol appears on the poster created by the China Anti-Tuberculosis Association in mid-1930s, with its basic message of “don’t spit” presented in a much longer, perhaps culturally more acceptable, Chinese text in a poster that tells a story. It reveals the connectedness of the anti-tuberculosis campaigns in many countries.

Although the NTA used fear-based warnings and moralistic advertising in their early decades, they later moved to more positive messages and images. One circular included: “Don’t ever spit on any floor. Be hopeful and cheerful. Keep the window open.”

Many posters in the exhibit deal with activities that are under the control of the individual. The recommendation to cover coughs and sneezes and the danger that an individual poses to the general population by possibly starting an epidemic will resonate with the public today. We, too, are in an era of the threat of a continued spread of respiratory infections and the threat of pandemic influenza or a more transmissible avian influenza virus. Although some posters showing ways to limit the spread of respiratory infection may have been aimed at limiting the spread of tuberculosis, the general message remains relevant and appropriate today because of shared mechanisms of transmission for many respiratory infections.

Posters developed to support tuberculosis control advocate the use of x-rays to discover unknown spreaders of infection. One poster shows a healthy-appearing middle class family—suggesting that anyone could be infected with tuberculosis. In the middle part of the 20th century (especially during the1940s and 1950s), mass chest x-ray screening programs were established in many cities, some employing specially equipped vans that toured the cities offering free chest imaging. Unfortunately, some screening programs used photofluorograms, photograms of fluoroscope images, rather than conventional x-rays. Apparently, many machines had no filters and no shielding, so screened individuals ended up receiving large doses of radiation. Although these mass screening programs detected some cases of unrecognized tuberculosis (some studies suggested that early programs detected about 20% of all cases of active tuberculosis), they also delivered radiation and its risks, which were not fully appreciated at the time. As the incidence of tuberculosis dropped, the yield from mass screening of the general population dropped and the approach was discontinued. Now routine screening x-rays are used only in selected populations with high risk of tuberculosis, such as prison populations in some cities or immigrants to the U.S. coming from countries with a high incidence of tuberculosis.

Some posters speak to the dangers from drinking unclean water at a time when many in the U.S. had come to take safe drinking water for granted. One poster, dating from 1944, suggests the risk of death from drinking unclean water in a jungle stream and advises soldiers to drink only approved water. By this time in the U.S., many municipal water systems had come to rely on filtration and disinfection to virtually eliminate waterborne infections like typhoid fever and hepatitis A. It is a sad commentary that safe drinking water remains unavailable decades later to about a billion persons globally, and waterborne infections continue to claim lives, especially in developing countries.

Mary Elizabeth Wilson, MD

Associate Clinical Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School

Associate Professor of Population and International Health

Harvard School of Public Health

About

An Iconography of Contagion

An Iconography of Contagion was on exhibition at the National Academy of Sciences in the year 2008, and was the result of a collaboration between the Cultural Programs of the National Academy of Sciences (CPNAS) and the National Library of Medicine (NLM) of the National Institutes of Health. The posters here, which are only a small sampling of the NLM’s collection, offer a glimpse of the visual system of iconography that was developed to communicate health concerns in the 20th century. From a historical perspective, the posters offer much more than originally intended. They are mirrors, reflecting the perceptions, biases and attitudes of the culture and era in which they were created.

J.D. Talasek, Director

Cultural Programs of the National Academy of Sciences

Curator: Michael Sappol, History of Medicine Division, National Library of Medicine

Contributor: Mary Elizabeth Wilson, Harvard Medical School & School of Public Health

Designer: Jonathan Ingram, i.design

Coordinator: Alana Quinn

Acknowledgements

Eva Åhrén, American Lung Association, Douglas Atkins, Roxanne Beatty, Liping Bu, Anja Blazun, Ralph J. Cicerone, Carol M. Cicerone. William Colglazier, Roger Cooter, Rachel Core, Todd Danielson, Elizabeth Fee, Harvey V. Fineberg, Kenneth R. Fulton, Mitja Kosnik, Jan Lazarus, Patrice Legro, Joan Mathys, Ruth Peyser, Barbara Pope, Nadgy Roey, Nils Rosdahl, William Schupbach, Erika Shugart, William Skane, Cheri Smith, Thomas Söderqvist, Claudia Stein, Sandy Taylor, Terrence Higgins Trust (London, England), Paul Theerman, Dan Todes, Charles M. Vest, Saska Zdolsek

You can view the original website which was created to accompany the display archived in the NLM Institutional Archives web collection. This site was developed in 2022 by Elizabeth Mullen, Winston Churchill, Carrissa Lindmark and Allison Cao with design by Astriata.

Watch a video on YouTube about the exhibition from the American Society for Microbiology.

An Iconography of Contagion traveled to two additional venues:

September 28, 2009 through January 29, 2010

Global Health Odyssey Museum, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

1600 Clifton Road, NE at CDC Parkway, Atlanta, GA 30333

February 15, 2010 through June 1, 2010

Claude Moore Health Sciences Library, University of Virginia

1350 Jefferson Park Avenue, Charlottesville, VA 22908

Explore blog posts about Posters

Explore blog posts about Posters  AIDS, Posters, & Stories of Public Health:

AIDS, Posters, & Stories of Public Health:  Explore blog posts about Infection

Explore blog posts about Infection