The World That Darwin Made

Eugenics

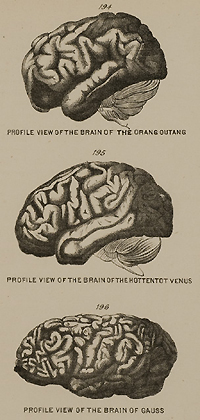

Evolution of the brain, in Henry C. Chapman, Evolution of life, 1873

Darwin’s ideas developed in ways that Darwin could scarcely imagine. His cousin, Francis Galton (1822-1911), coined the term eugenics for a science that hoped to “improve” the human species through “the self-direction of evolution”; its most extreme followers promoted forced sterilization and genocide. Though now associated with the abhorrent and discredited policies of the Nazi state, before World War II eugenics had a wide following among scientists, politicians, and writers around the world. The leading student and promoter of eugenics in the United States for over a quarter century was Charles Davenport (1866-1944), director of the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory’s Eugenics Record Office from 1910 to 1940, part of the Station for Experimental Evolution. His works provided a scientific sheen to policies ranging from immigrant exclusion to forced sterilization of the “feebleminded.” Others who supported eugenics included inventor Alexander Graham Bell; Stanford president, ichthyologist, and peace activist David Starr Jordan; novelists Émile Zola and H. G. Wells; U.S. presidents Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson; playwright George Bernard Shaw; and birth control activist Margaret Sanger. The alliance of eugenics and progressive politics was evident, in the need to exert rational control in pursuit of the common good. The eugenics movement attracted social activists such as Moses Harman (1830-1910), who pursued his goal through The Eugenic Magazine. Harman was a supporter of free-thought (i.e., anti-religion), free love (i.e., outside marriage), feminism, and anarchism; successes in these endeavors would uplift the entire human race, he thought. Today eugenics exists only in a narrow medical context—for example, by identifying carriers for Tay-Sachs disease, a recessive metabolic disease.

Last Reviewed: May 7, 2014