The World That Darwin Made

Social Science continued

The anarchist philosopher, Peter Kropotkin (1842-1921), also claimed that Darwinian evolution governed society, but he emphasized the evolved trait of spontaneous assistance. His book, Mutual Aid: A Factor in Evolution (1902), was to be a corrective to overly competitive models, and its ideas supported his anarchist views that natural work for the common good would emerge once older oppressive social forms were gone.

Darwin’s influence is also seen in the work of pioneering sociologist Max Weber (1864-1920), who described the complex interplay between ideas and society in such works as The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (1904/5). No less than Darwin, Weber saw that mental and material forms developed in conjunction with one another—that religious and cultural expressions could lead to entirely new ways of structuring societies and economies.

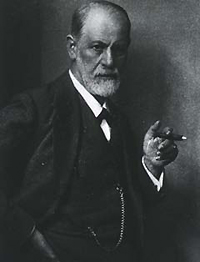

Sigmund Freud (1856-1939), 1914

Sigmund Freud (1856-1939) worked on similar tracks in charting the human psyche. After studying anatomy and neurology, he devoted himself to the dynamics of human consciousness, seeing these as fully natural phenomena. The human moral sense, for example, far from reflecting a divine image, was instead a naturally evolved brake on human aggression that allowed whatever peace and progress that might be attained among a warlike species. Human character became a carefully negotiated balance among psychic forces, which maintained an uneasy truce among one another.

In a similar manner, Franz Boas (1858-1942), the “Father of American Anthropology,” worked solidly within the Darwinian tradition by denying a rigid and progressive cultural evolution that ranked societies on scales of achievement. He promoted instead the study of the ongoing, fluid, and dynamic adaptation of humans to their social and natural environments.

Last Reviewed: May 7, 2014